BEIJING, Nov. 29, 2022 /PRNewswire/ — “We must do our part by finding our passion, dreaming big, then starting small, and loving others along the way, and we can absolutely take our impact on the world to a whole another level,” said Geresu Dagmawit Mesfin in the final of the fourth China Daily Belt and Road Youth English Speaking Competition, held online from Nov 26 to 27.

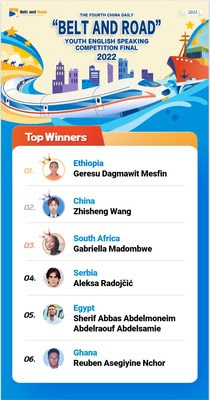

Mesfin, 24, of Ethiopia and Wang Zhisheng, 21, of China, and Gabriella Madombwe, 19, of South Africa, were the three winners among six contestants who reached the final. Nearly 40 young people in more than 30 countries and regions had taken part in the semi-final.

Speaking on the topic “Youth making a difference”, all finalists talked of how young people can contribute to making the world a better place by proposing and making positive changes.

In Wang’s speech, he calls on young people from every inch and crevice of the world to contribute to a better future for this planet for all human beings to share. “I believe, there is a huge difference youth can and should make.”

“Youth is seeing the world through your own lens, an unperturbed lens which has not been smudged by the restrictions of reality,” Madombwe said. “Optimism, hope, courage, idealism, energy – that is how I see youth.”

Concluding the final competition, one of the judges, Mark Levine, a professor at Minzu University of China, spoke highly of the event and the contestants.

“This was a very unique competition, extremely interesting and informative. People came from all over the world. ”

The China Daily Belt and Road Youth English Speaking Competition, first held three years ago, has been an important public platform for young people from all over the world to exchange ideas, deepen mutual understanding and polish their communications skills. The annual event has attracted participants from 51 countries and regions.

This year’s event began in January. Preliminary rounds were held offline in Malaysia, Russia, Serbia and South Africa, and nine universities in China. With this year’s event over, contestants will get the chance to take part in more activities so they can gain a deeper understanding of China linguistically and culturally.

Photo – https://mma.prnewswire.com/